DJANGO REINHARDT, JULIEN’S AUCTIONS, AND A LEVIN GUITAR

An article I wrote about Django Reinhardt and a guitar connected to him was just published in the Worthpoint newsletter view it here or enjoy it below.

DJANGO REINHARDT, JULIEN’S AUCTIONS, AND A LEVIN GUITAR

“Django, c’etit la musique fait l’homme”

(Django was music, made man)~ Emmanuel Soudieux

In 1946, at the Aquarium, a jazz club in New York City, photographer William Gottlieb took photographs of jazz great Django Reinhardt playing a guitar. These photographs have become some of the most popular images of Django. However, the guitar he is holding did not belong to him; it was borrowed for the photograph from Fred Guy, rhythm guitarist for the Duke Ellington Orchestra.

On May 20, 2017, Julien’s Auctions will sell this Swedish-made Levin guitar. It is one of only a few pieces of property ever to be auctioned with an association to Django Reinhardt. The following is a brief history of Django Reinhardt’s life and his connection to Ellington, his journey to the United States, and the fateful guitar.

Django Reinhardt was born Jean Reinhardt on January 23, 1910, in the Belgian village Liberchies. His father Jean-Eugéne was a musician, juggler, basket weaver and his mother was a dancer or jewelry maker, depending on what was called for. They followed a traditional Romani lifestyle of seasonal travel around Europe. They just happened to be in Belgium when his mother, Négros (Laurence Reinhardt), gave birth to Django in the back of their caravan while Jean-Eugéne performed at a local inn.

Legal names for Roma people are not that important; they were provided for paperwork required by governments. A family name, a Romani name, is what is used more commonly. These names are descriptive, “Bear” or “Violet.” Django’s sister Sara was referred to as “Claw” purportedly for holding her own with her brothers during fights. Négros dubbed baby Jean, Django. This is not a common Romani name. It means “I awake.”

Django’s first instrument was a violin. Violins are portable, versatile, and traditional among Roma musicians. He began learning music from his family. This was not formal training and Django never learned to read music. He eschewed school and did not learn to read or write until much later in life. Music he learned early, by ear.

At 10, Django encountered a banjo and was fascinated. At 12, an acquaintance saw Django’s interest and gave him a banjo of his own. Django’s busking brought in much needed financial help for the family. Jean-Eugéne left them and Négros was providing for her children on her own. Soon 12-year-old Django was hired to perform in the dancehalls of Paris, which he did until the age of 18.

At 18, Django was a married man expecting his first child with his first wife. On October 26, 1928, Django excitedly returned home, eager to tell his pregnant wife about an opportunity to perform with a new orchestra. As he entered his caravan, a candle was knocked into a pile of cellophane flowers his wife had made. The highly flammable cellophane ignited a fire. Django was able to push his wife to safety but sustained extensive burns, including disfiguring burns on his left hand.

The doctors told Django he would never play music again. And whether it was from Django’s stubborn arrogance or the will to survive in a life that would be worthless without music, Django slowly and secretly re-learned how to play guitar. The music would be singular to him – his ring and pinky finger were largely paralyzed, leaving him his thumb, index and middle finger to chord the frets. Over his six months of convalescence Django created a new style of playing.

After his recovery, he continued to travel and to perform; meeting musicians and admirers who would help shape his career. He was also introduced to Jazz. It is reported that when Django heard Louis Armstrong for the first time he wept, and repeated the Romani phrase “Ach moune! Ach moune!” (My brother! My brother!) over and over. A love affair with jazz began. Duke Ellington is quoted as saying Django was “(T)he most creative jazz musician to originate anywhere outside of the United States.”

Django gained recognition with the Le Quintette du Hot Club de France who performed and recorded together in the 1930s. As an all-string jazz band they were unique to jazz – the jazz of the West was horn-based. The Quintette would have several line-ups but at its heart were Django and violinist Stéphane Grappelli. Initially, the band was a side project, developed out of a backstage improvisation. With the support of the Hot Club de France and jazz fans around Paris, the Quintette began performing and recording.In 1939, Duke Ellington was touring Europe and came to Paris. Django played for Ellington at the Hot Club and then later jammed with him at a smaller club. The pair hatched plans for Django to come to the US and tour with Ellington. Before those plans could come to fruition, World War II began.

As an ethnically Romani person and a performer of jazz, Django had two strikes against him with the Nazis. When Hitler began his murderous campaign, it was the Roma people he targeted first. Over the course of the war 600,000 Roma would be murdered. Jazz was vilified in Nazi propaganda and condemned as “degenerate music.” But it was music that German officers secretly liked, and Django benefitted from their patronage and protection.

Django not only survived the war, he managed to thrive, arguably achieving the zenith of his career. His song “Nuages” (Clouds) became hugely popular, almost an anthem for occupied Paris. Django’s image was sold on street corners throughout Paris. But still, he lived in fear of the Nazis who were surveilling and imprisoning his fellow Roma and jazz counterparts. When an invitation came from the Nazi High Command in Paris for Django to perform, he stalled until they would be put off no longer and then he fled rather than perform.

Despite arrests and failed attempts to flee France, Django and his family withstood the war. The invitation to go to the United States was renewed and on October 1946, Django Reinhardt arrived in New York to perform with Duke Ellington and his orchestra. Thirty-six-year old Django traveled alone and arrived with no luggage, not even a guitar. He was convinced that given his popularity as “the World’s Greatest Jazz Guitarist,” luthiers across America would line up to give him a guitar. Django was blissfully unaware that he was not a household name in the US.

William P. Gottlieb/Ira and Leonore S. Gershwin Fund Collection, Music Division, Library of Congress

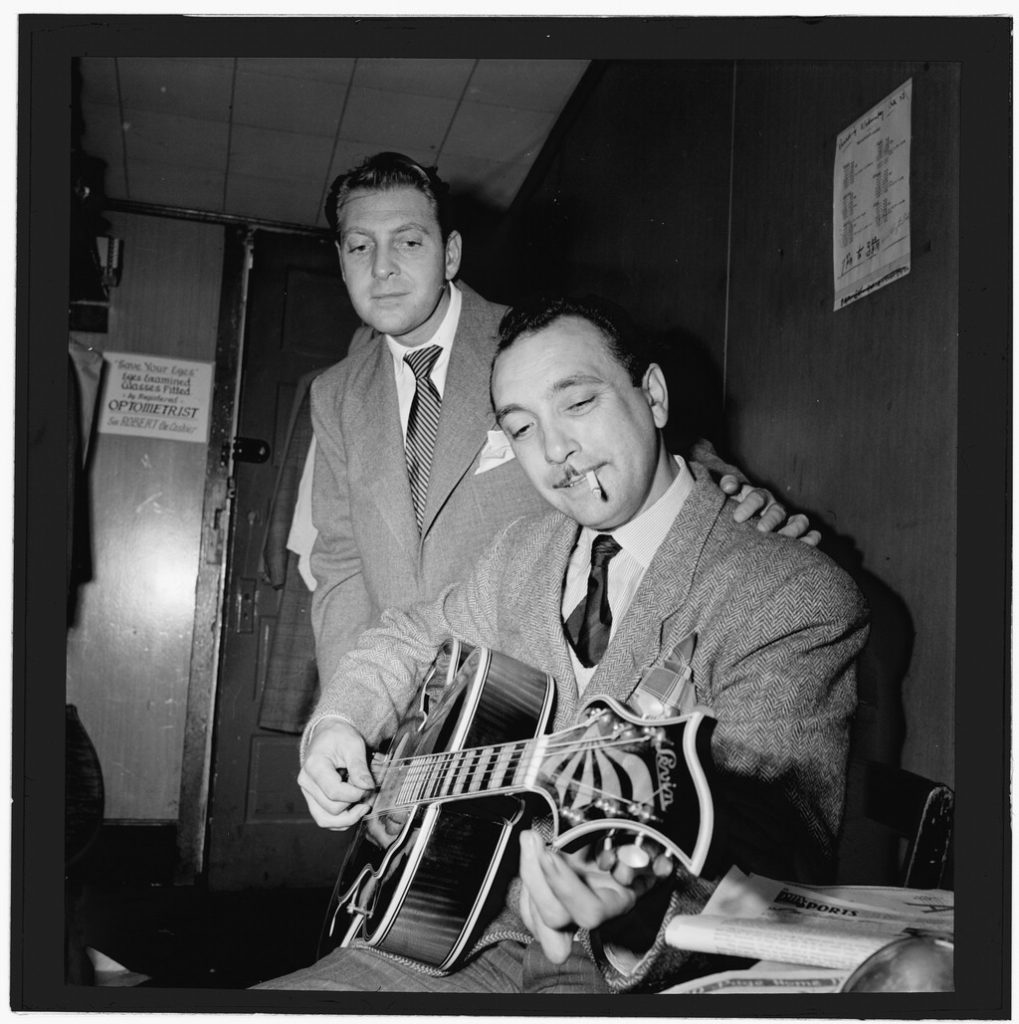

The day after Django arrived, Down Beat magazine sent reporter and photographer William Gottlieb to the Aquarium to meet Django. With Django’s limited English skills Gottlieb said it was hard to get an impression of Django’s personality. He decided to focus his photographs on what he saw as the most interesting thing about Django – is hands. Django used Fred Guy’s guitar as a prop to pick on. The images Gottlieb took that night were published on the cover of the magazine and are now some of the most famous images of Django.

Fred Guy rhythm guitarist in the Duke Ellington Orchestra with his Levin guitar as photographed by William Gottlieb.Photo credit: William P. Gottlieb/Ira and Leonore S. Gershwin Fund Collection, Music Division, Library of Congress

Fred Guy had purchased the guitar while touring Europe with Ellington in 1939. In April 1939, the Duke Ellington Orchestra performed numerous concerts throughout Sweden, including Göteborg on April 4 and again on April 30. While in Göteborg, Guy purchased the Levin De Lux archtop.

There is no record of what Guy and Django thought of each other; or how they worked together. The guitarists likely met in Paris, perhaps even performed together. Guy, as Ellington’s longtime rhythm guitarist, would have most likely backed Django during his 1946 US performances. They shared a similar music history; both began their musical careers on the banjo. Whatever the relationship, Guy lent Django his guitar for the historic photographs.

Ellington had arranged for performances in 21 cities over the course of one month, culminating in performances at Carnegie Hall. The tour zig-zagged around the East coast and Mid-West. Django was a literal and musical surprise to most audiences. His presence hadn’t been advertised because it was unknown if he would arrive to perform. His guitar playing was the second surprise – it was a sound unlike anything most US audiences had heard before. Ellington was generous to his French friend, allowing him to steal the spotlight and working around his idiosyncrasies. Django was not much for practice; he sometimes overslept, and when performing in France some nights he didn’t show at all. For Ellington, Django had mostly arrived on time. Except for one of the most important of nights.

Django was scheduled to play two shows with Ellington at Carnegie Hall. These programs were well advertised and according to one reviewer on the first night “The hall was packed out. I can safely say that by far the greater part of the audience was made up of admirers who had waited for this moment for 10 years.” Django took six curtain calls that night.

Django Reinhardt and David Rose photographed by William Gottlieb at the Aquarium.

Photo credit: William P. Gottlieb/Ira and Leonore S. Gershwin Fund Collection, Music Division, Library of Congress

The following night Django was to perform at 10:30pm. When he didn’t arrive Ellington continued playing until he could no longer put off apologizing to the crowd and telling them that Django would not perform. At 11pm Django arrived but without a guitar. A guitar was found but the entire performance was a disappointment and an embarrassment for Django. He remained in New York for another month performing at Café Society, but when his 60-day visa was about to expire, he returned to France, homesick and feeling as though he had not conquered America.

Django returned to France a new performer. He was influenced by the music he heard in the West and this transformed his style from swing to modern jazz. In the following years his relationship to music and his popularity waxed and waned. In 1950, he hung up his guitar for a while and spent time with his family, returning to a more traditional Romani life.

In 1951, saxophonist Hubert Fol came looking for Django and coaxed him back into performing. This return to music lasted until May 16, 1953. On that day, at age 43, Django died of a cerebral hemorrhage. The funeral service was performed in a typical tradition for his family including the burning of the deceased caravan and all of their worldly possessions.

Django Reinhart had a wild personality and full life – much of which could not be contained in this small article. Missing is the story of the love of his life, his son, the family monkey, stolen chickens, many talented collaborating musicians, more than 550 recordings, and an influence that spread to musicians around the world.

The Levin guitar will be auctioned by Julien’s on May 20, 2017, during the Music Icons Auction at the Hard Rock Café in Times Square, only blocks away from the former site of the Aquarium where Django was photographed by William Gottlieb.

When the Levin guitar is sold on May 20, 2017, during the Music Icons auction at the Hard Rock Café in Times Square, it will be only blocks away from the former site of the Aquarium where Django was photographed by William Gottlieb.Please join Julien’s for the historic sale live or online. For more information please visit juliensauctions.com or call 310.836.1818.

[Writer’s note: The Roma people, of Romani culture, are often inaccurately called “Gypsies.” This is an exonym at best and a racial slur at worst. The term originated in Europe when it was believed that the Roma people came from Egypt. The author has attempted to use the correct terms, correctly, for this article.]

Megan Mahn Miller is an appraiser and owner of the consulting and appraisal service, Mahn Miller Collective Inc. which specializes in Rock ‘n’ Roll and Hollywood memorabilia. Mahn Miller is also a Property Specialist with Julien’s Auctions.